Generation of Hope

Generation.

noun. The average time it takes for a child to grow up, reach adulthood, and have children - typically 30 years

verb. A stage of technological development or innovation

noun. A group of people living at the same time or of approximately the same age

Inception.

1993 was a generation ago.

Before the human genome was sequenced.

Before the internet was worldwide.

Before BRCA genes were discovered.

Before immune checkpoint inhibitors, patient-reported outcomes, epigenetics, Twitter.

In 1993,

we were 10 years away from solid proof of a link between cancer and obesity and 20 years away from tracking cancers in liquid biopsies.

In 1993,

Sam Broder, MD, was head of the NCI, Chuck Coltman, MD, was the head of SWOG, and four of Jill Biden’s friends died of breast cancer. She vowed to do something about it someday.

In 1993,

cancer research was expanding and exciting, fueled by the funding and focus unleashed by the National Cancer Act signed into law two decades before. One generation had invested in the next generation, and we were reaping the benefits.

1993.

This was the year Francis Collins, MD, PhD, took over what became the Human Genome Project.

This was the year the FDA approved paclitaxel, with rituximab right behind.

This was the year that National Cancer Institute and NASA officials reviewed the first proposals to develop digital mammography.

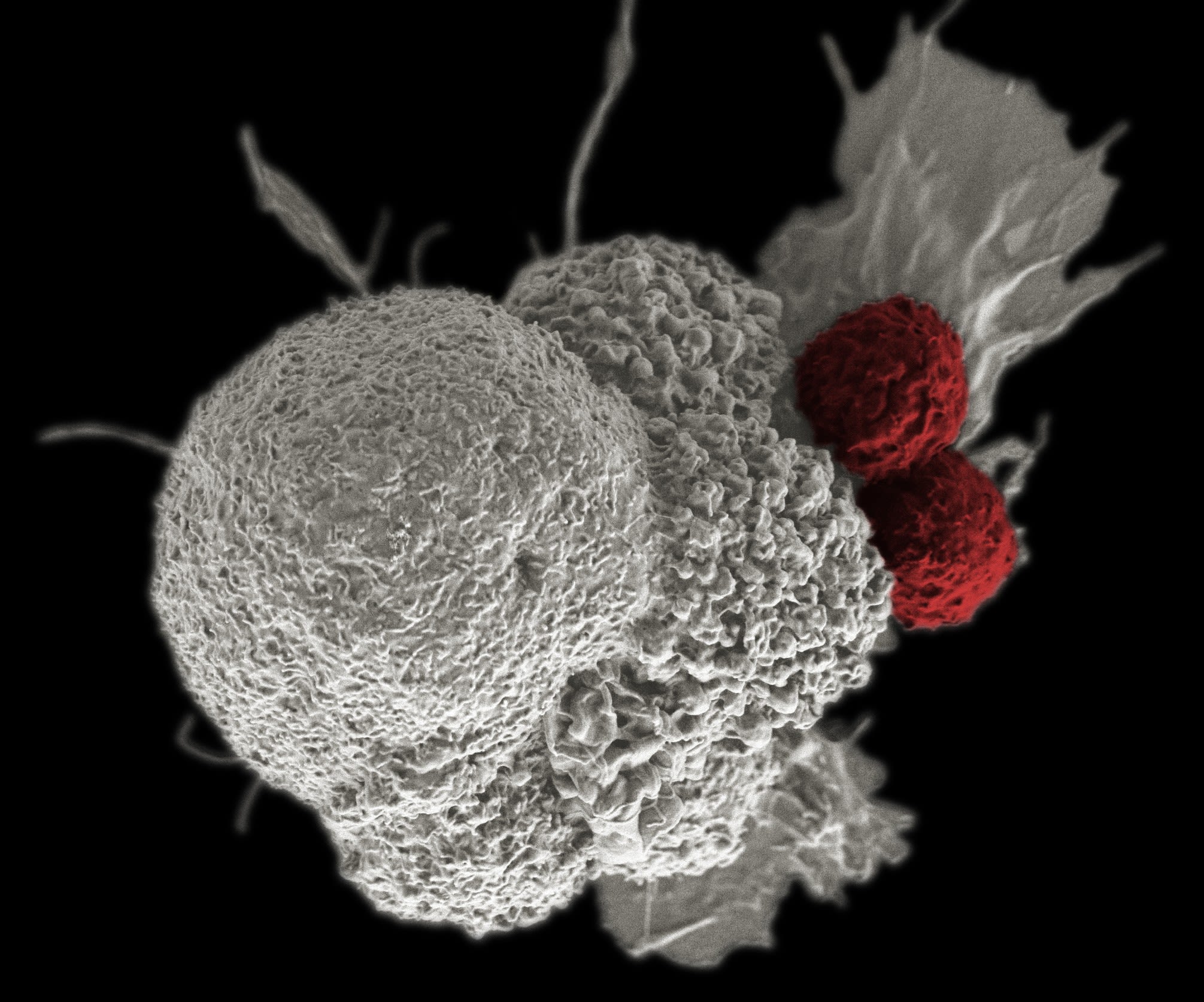

And in a modest lab at UC Berkeley, an irreverent, harmonica-playing researcher named Jim Allison identified CD28, a protein that plays a key role in triggering the body’s immune response to cancer. Immunotherapy was about to be born.

In 1993, SWOG made history. The group launched the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial, the largest clinical trial ever to study the disease.

Ambition was in the air.

Chuck Coltman was all Texas – a tall man with a booming voice and big ideas. He would go on to create the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, the world’s largest breast cancer meeting, and advocate for translational research and patient advocacy. But in 1993, Coltman had money on his mind.

At the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, he brought in big donors – cattle ranchers, car dealers. He was certain SWOG could bring in big donors, too, and duplicate the success that Denny Hammond, MD, of Children’s Cancer Group had in creating a foundation. He called together SWOG greats including Drs. Rich Fisher, Jack Macdonald, and Larry Baker – and cannily included Lt. Col. George Ensley, who earned a Purple Heart in Korea and had just retired as deputy CEO for USAA, the financial services company catering to the military. Ensley was committed to spend his retirement serving San Antonio and raising money for local charities.

“Chuck invited a bunch of us down to San Antonio,” Baker remembers. “And Brian Chavez, the first executive director, he was there. Brian and Chuck took us to a theme park – yes, a theme park – and pitched the idea of a foundation. We could raise money from our members and corporate sponsors like USAA. We could use that money for research and to create a permanent base for SWOG operations in San Antonio. We were light on ideas of how it all would function, but we went ahead.”

Charles A. Coltman, Jr., MD (right) with statistician John Crowley, PhD.

Charles A. Coltman, Jr., MD (right) with statistician John Crowley, PhD.

John Crowley, PhD

John Crowley, PhD

John Crowley, PhD, SWOG’s first biostatistician, said the motivation was practical.

“We wanted money for our trials,” Crowley said, “and this was a way to get it.”

On April 24, 1993 in Denver, the Southwest Oncology Group board of governors elected the first board of directors for the Southwest Oncology Group Foundation, a group that included Baker, Crowley, Fisher, Macdonald, and Ensley.

The generation of Hope had begun.

Acceleration.

On a sweltering Sunday in September 1998, about 150,000 people gathered on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. for an unprecedented rally for cancer research. “The March: Coming Together to Conquer Cancer” had one goal: increase funding for the National Cancer Institute.

The march marked the dawn of a new generation, that of cancer patient advocacy. Survivors or people who’d lost loved ones – children, parents, siblings, friends – saw what AIDS and abortion rights activists accomplished. Now it was their turn. Fashion magnate and film producer Sidney Kimmel, who would go on to donate millions to cancer causes, helped fund the event. Aretha Franklin performed on the main stage and luminaries flocked to the mall: Vice President Al Gore, supermodel Cindy Crawford, retired Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf.

Kimmel, baking in 80-degree heat on the stage, pointed a finger at the Capitol building and said:

“On behalf of 8 million cancer survivors, on behalf of all of us, good God, what the hell are you waiting for?"

Kimmel and the advocates scored a victory. The NCI budget nearly doubled from $2.5 billion in 1998 to $4.6 billion in 2003. For a brief, shining moment, members of Congress put their foot on the gas pedal of cancer research funding. So did the Southwest Oncology Group Foundation.

In 1998, Brian Chavez was named executive vice president and chief executive officer, and changed the name of the nonprofit to The Hope Foundation. He ramped up – and glammed up – fundraising by courting celebrities like tennis star Pete Sampras and organizing raffles and cocktail parties at SWOG group meetings. Chavez raised money from USAA, car dealerships, banks. In 1999, Ortho Biotech became the first official sponsor of a new foundation program – the Young Investigator Training Course.

This next generation support was prescient.

While the flush of NCI funding was a boon to researchers – like the 30 percent increase in the size of R01 grants – it also posed challenges. Universities and cancer centers used the extra NCI funding to build new programs and hire more faculty – who then submitted an avalanche of grants. New grant applications to the NCI increased 40 percent. Then the agency’s budget flat-lined from 2004 to 2008. In 2008, in a perspective piece in Molecular Oncology, a writer described the effect this way: “In essence, the increase and then leveling off of funding has jolted research funding as brakes to a speeding car.”

The number of funded NCI applications dropped from 32 percent in 1999 to less than 20 percent in 2007. Richard Schilsky, MD, who in 2008 was serving as ASCO president, reported that the cooperative groups were taking a hit. Groups were shutting down entire research programs in areas like brain and pediatric cancers, postponing up to 100 clinical trials, and struggling with a decline in recruitment to 3,000 patients per year.

“We really need to get funding for cancer research back on track,” Schilsky said, “to move forward in the fight against cancer.”

2005.

Larry Baker could not control the NCI, but he did oversee SWOG and The Hope Foundation. When he became group chair in 2005, Baker came in with the zeal of a reformer, swapping glitz for rigor. He wanted the foundation to run like an NCI review committee, with clear expectations and formal procedures and subject matter expertise.

Dott Freeman, PhD, a sharp-witted, charismatic woman, was Hope’s sole employee. Freeman began working on the foundation’s first fundraising plans and needed help on the grantmaking side. She hired a tall redhead named Johanna Horn, who was tasked with creating program descriptions, application procedures, review panels.

And so, while the world outside Hope contracted, the world inside Hope expanded.

Laurence Baker, DO

Laurence Baker, DO

In 2006, Hope funded a conference in Guatemala to design SWOG’s first international trial, a meeting that attracted an up-and-coming gastrointestinal researcher – Charles Blanke, MD.

In 2007, Hope appointed Jo Horn as executive director.

In 2008, Hope created SWOG-CTI to lead industry partnerships.

In 2009, Hope expanded their footprint in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

In 2010, Hope took control of SWOG operations.

In 2011, Hope earned a 4-star Charity Navigator rating, the top honor for effective charities.

In 2012, Hope established bylaws to increase transparency and accountability that set board member term limits, created evaluation procedures for the executive director, and formed finance and governance committees.

Expansion.

Anne Schott, MD, finished her fellowship in 1996. Opportunities in academic medicine were hard to find and harder to get. But once you landed a job, you got something precious.

“Protected time,” Schott says. “My generation had protected time – the next generation didn’t. It became clear to me and others that we needed to provide it. If you wanted to be a physician scientist, you had to carve out time outside the clinic. Hope recognized that right away.”

As a Hope board member, and SWOG executive officer, Schott helped support the growth of the Young Investigator Training Course and the establishment of the Dr. Charles A. Coltman, Jr. Fellowship Program.

Later, in 2020, Hope launched the John Crowley, PhD, Award for statisticians. In 2022, Hope introduced the Nicholas J. Vogelzang, MD, Scholarship for early-stage genitourinary researchers to honor a legendary teacher, mentor, and physician. Hope also sent early-stage investigators to group meetings – and to a virtual grant-writing course specifically designed to bring in awards at the start of their careers.

Year after year, Hope endured, offering these young investigators opportunities to focus, learn, and earn support and funding for their ideas.

Another year, another round of awards.

Another year, another round.

Another year, yet another.

Then a couple of decades pass – and an entire generation of cancer researchers has inherited mentorship, sponsorship, partnership, friendship.

Virginia Sun, PhD, MSN, RN, got all these gifts when her mentor, Robert Krouse, MD, MS, extended an invitation in the halls at City of Hope, the southern California cancer center.

“Hey Virginia, come join. It’s a great group!”

With that, the new nurse scientist attended her first SWOG meeting. It was spring 2015 in San Francisco. The group was rebuilding its nursing subcommittee, and Krouse thought it would be a great networking opportunity. Sun had just been hired at City of Hope, and she and Krouse were talking about a trial idea. "If you want to do trials," he said, "SWOG’s the place."

Sun was delighted by the meeting. She was introduced to people from all over the country who were interested in the same thing – cancer discovery. So much talent and wisdom and curiosity in these rooms, she thought. So many people, from so many disciplines and institutions, willing to give you feedback on your ideas and ask for your opinion about their theirs. It was thrilling.

The next year, in 2016, Sun was accepted into the Young Investigator Training Course held every year in Seattle. It was one of the few all-female cohorts since the course was founded in 1999. As all YITC attendees do, Sun brought a trial idea to workshop. She wanted to test whether a diet coaching program would improve the bowel function of rectal cancer survivors. Mike LeBlanc, PhD, SWOG's group statistician, was encouraging. “Collect more preliminary data,” he counseled.

She did – with another Hope grant. With those findings, she won a $275,000 R21 grant from the NCI. Then she got even more Hope funding to help launch the study. SWOG opened S1820 in 2019, closed it in 2022, and results are in now preparation for publication.

Sun is now a full professor at City of Hope and a SWOG executive officer.

“Having people hold your hand in the beginning, and walk you through the process of creating a clinical trial is critically important,” she says. “The system can be so overwhelming and so complex. I’m so grateful for all the investments Hope made in me.”

Katherine Crew, MD

Katherine Crew, MD

Hope can claim dozens of cancer researchers as success stories, including SWOG leaders Drs. Dawn Hershman, Cathy Eng, Lynn Henry, and Kathy Crew.

Joseph Unger, PhD

Joseph Unger, PhD

Hope also nurtured the next generation, science stars like Drs. Monty Pal, Megan Othus, Joe Unger, Kevin Kalinsky, Melissa Accordino, Neeraj Agarwal, Sarah Goldberg, Jennifer Klemp.

Kevin Kalinsky, MD

Kevin Kalinsky, MD

Meeting by meeting, course by course, grant by grant, Hope nurtures researchers. String these researchers together, and you get a generation of discovery, a never-ending inheritance of hope.

Integration.

By 2012, Jo Horn had led Hope for five years. Under her direction, the charity built a reputation for credibility and consistency, flexibility and creativity. Hope was no longer what Horn calls “candy in the parade.” Hope was the marching band, the drum corps, and the color guard all in one – a driving force for developing SWOG leaders and launching SWOG trials.

“We have a certain agility, a capacity to be like water,” Horn said. “We can direct support where and when it is needed. The NCI grant comes around every five years. But Hope is there every year, working with SWOG leadership, to not only fill in gaps but drive progress.”

Charles Blanke was elected grand marshal of the parade in 2012, and took over as SWOG group chair the next year. For the next decade, Blanke and Horn and their leadership teams directed foundation resources to address the two urgent imperatives of modern cancer clinical trials: complexity and diversity.

When Hope began, trials were fairly simple: Compare one chemotherapy treatment to another, one combination therapy against another. What’s better? A or B?

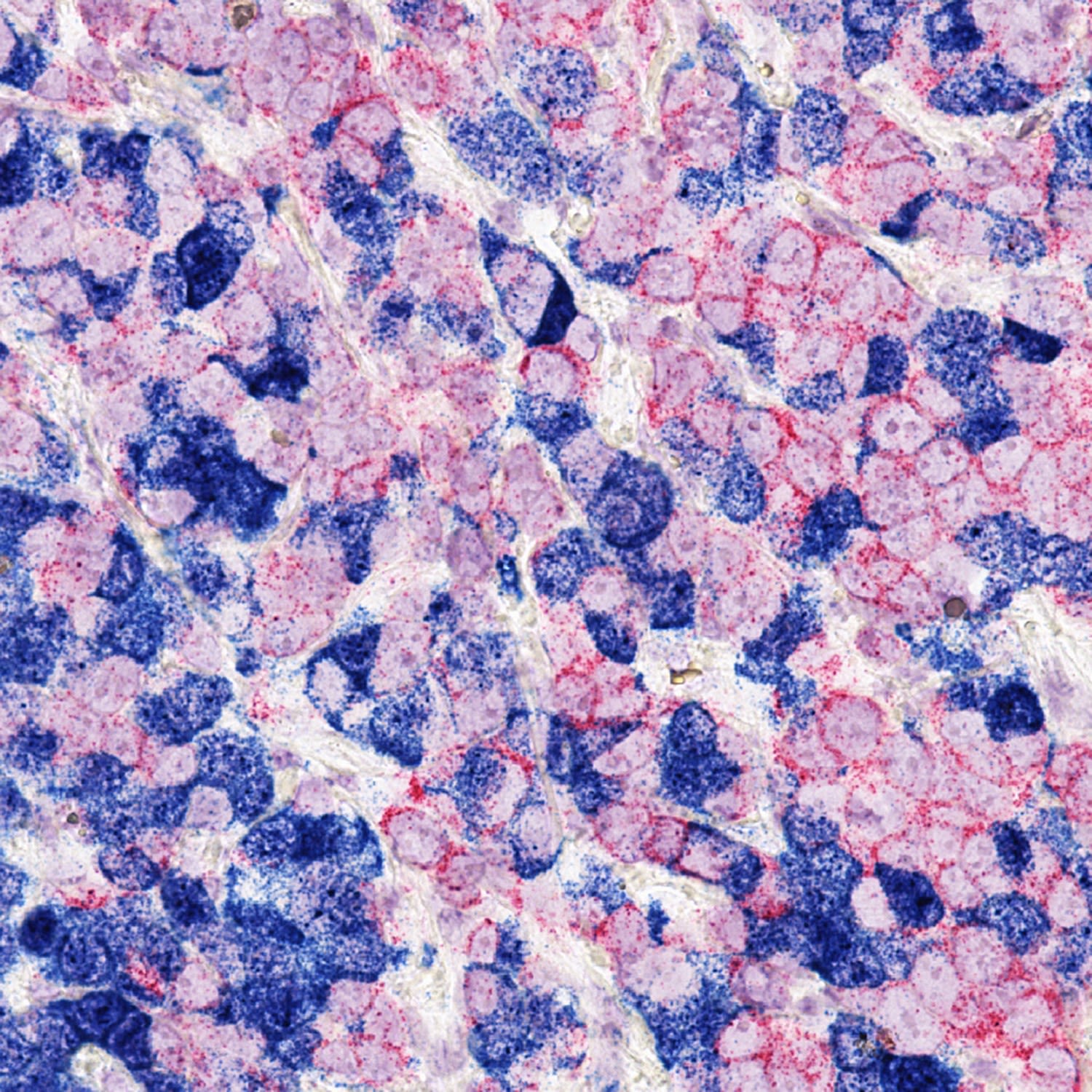

Then the revolutions in genetics and computing arrived. Sequencing the human genome, and creating computers to rapidly “read” this code, allowed scientists to identify hundreds of genetic changes that cause cancer to start, grow, and spread. Drugs were created to target those specific changes, along with tests to identify them in a patient’s blood or tumor cells. The result: An entirely new paradigm for understanding cancer, developing targeted therapies to fight it, and matching those regimens to the right patients. This is precision medicine – and it radically remade cancer trials.

Dana Sparks had a front seat to the revolution. As the leader of the SWOG protocol and operations office in San Antonio, Sparks saw trials spike in complexity.

Managing genetic samples required new infrastructure, new collaborators, and specialized expertise in trial design, data and protocol management, and biostatistical analysis. To adapt, SWOG launched a biobank, partnered with Jackson Laboratory and Cold Spring Harbor scientists, and expanded its protocol team. Hope made major investments in translational medicine, launching the SWOG Trial Support program to pay for supplies like biospecimen collection tubes and pledging $1 million to the SWOG Statistics and Data Management Center. This unprecedented investment allowed the stats center to staff up to meet the demands of new trial designs, an avalanche of biological specimen and imaging information, and a massive spike in patient reported outcomes, a new tool to understand adverse events, side effects, and quality of life for patients enrolled in cancer trials.

Today, Sparks estimates that nearly 100 percent of SWOG drug trials include tumor, blood, or other biological sampling, and about 20 percent of all SWOG trials include patient reported outcome questionnaires. Work once captured on paper now sits in massive computer servers. In the last decade, the size of Sparks’ staff more than doubled.

Sparks says Hope has allowed SWOG to not only manage trial complexity but also promote trial diversity. Inclusion, she says, is the foundation’s greatest achievement.

“Hope built a bigger table for cancer research, and we’re better for it,” she said.

Inclusion takes many forms in cancer research. Perhaps the most powerful new players are patient advocates.

Using lessons from AIDS activists, cancer survivors used their voice in the 1990s to influence research – both its direction and its funding. In 1996, just two years before the historic cancer march in Washington, the NCI established its patient advocacy office. At SWOG, Baker brought on some of the group’s earliest advocates. But it was Blanke, along with inaugural advocate chair Rick Bangs, who expanded the group’s size, sophistication, and influence. SWOG now has the largest, most diverse patient advocate group in the National Clinical Trials Network. It’s Hope that supports them with training and travel opportunities.

Hope also sends clinical research associates, nurses, advanced practice providers, basic scientists, and pharmacists to meetings. Hope has supported landmark research on health disparities, and efforts to include staff from rural hospitals and institutions that serve large numbers of people of color. Hope funded SWOG’s plain language efforts and, in 2022, the creation of a new vice chair position for diversity, equity, inclusion, and professional integrity.

In a ground-breaking partnership, Hope garnered the support of Genentech to fund some of this work. It marks the first time the foundation engaged a biotech company not to run a trial but to improve all trials. Together, Genentech and Hope were creating a new culture.

Diversity takes many forms, including diversity of experience. Bringing trials to military veterans is one decision Blanke is most proud of making.

“One of the biggest changes to oncology research was getting veterans involved again,” he said. “Because of Hope funding, we were able to pilot VA research, and that attracted NCI attention. Now there’s a national program – NAVIGATE – which holds astonishing promise.”

Integration – of all these clinical trial pieces, all these clinical trial players – is perhaps Hope’s most important role. And their most powerful act of integration is to help host SWOG meetings.

For three days, first in spring then again in the fall, the entire team comes together from across the country and around the world to sit around tables to drink and debate, eat and dream, share small talk and big ideas. The coffee and wine, the conference rooms and committee dinners, are paid with dollars raised by Hope.

Laura Esfeller attended her first SWOG meeting in 2022 in Chicago. There, she met the man who helped save her life.

Connection.

Monty Pal, MD, was precocious, finishing high school at 13 and entering medical school at 17. In 2011, two years out of fellowship, he attended the SWOG Young Investigator Training Course. He came in with a prostate cancer trial idea, but would ditch it for a kidney cancer concept that became S1500 – the trial that established cabozantinib as the standard of care for metastatic papillary kidney cancer.

This was Laura Esfeller’s disease.

At 28, she was a young mother of two and a marketing ace for casinos. She just got a promotion at Caesars Entertainment and was riding high in Las Vegas. Then she began to notice abdominal pain and felt a fatigue so profound she would sometimes sleep in her car during lunch breaks. Her blood pressure spiked and the abdominal pain became blinding back pain. Her legs swelled so badly she had to wear a dress for her 29th birthday dinner. A couple of days later, she and her husband went to the emergency room. She took a blood test and got a CT scan. It revealed Stage IV kidney cancer – a tumor so large it was bigger than her kidney.

Esfeller was shocked. She was too young to get cancer. She had surgery to remove the tumor and a biopsy revealed that she had hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer, a rare condition that can cause muscle tumors and fibroids – and an aggressive form of kidney cancer.

That aggressive cancer would return, scattering like buckshot throughout her body. A scan showed tumors in her liver, lymph nodes, and both lungs.

“I will be dead in a year,” she thought.

Esfeller was referred to Nick Vogelzang. It was the start of a long and close relationship. Like Esfeller, Vogelzang received a cancer diagnosis early in life. She liked him immediately and trusted him implicitly. The medical oncologist spoke to her with warmth and honesty and respect. They laughed a lot. When presenting her with treatment options, Vogelzang was blunt. There is no standard of care for your disease. Get on a clinical trial. I suggest you enroll in this one. It was S1500.

Vogelzang told Esfeller that, as with all clinical trials, they could not choose which drug she would get. He’d hoped it was cabozantinib, which showed promise in earlier studies. When the results of her randomization came in, he walked into the room and announced: “You hit the jackpot!” She would be taking cabo.

Which she did. For more than three years. And she felt awful. The white lozenge she took every morning before breakfast brought crippling bouts of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Her skin turned pale and her hair turned white. Her blood pressure skyrocketed again and she developed blood clots.

But after an extended medical leave, she felt well enough to work again, in the office in mornings then at home in the afternoons. In December 2016, after just three months on cabo and just 10 days before Christmas, she went in for the first scan called for under the trial protocol.

When Vogelzang walked in the room with the results, he said: “80 percent.”

“What do you mean?” she asked. “80 percent what?”

“You have an 80 percent reduction in your tumor burden,” he said.

She jumped up and hugged him.

Just seven months later, she heard the sweetest four words a person with cancer can get: No evidence of disease. She would go on to work as a patient advocate, watch her oldest daughter graduate from high school, travel to Mexico and the Bahamas, and, in September 2022, mourn the death of Nick Vogelzang.

Just 30 minutes after she learned that he’d died at home in Las Vegas, when she was still crying from the news, she got a phone call from Rick Bangs, the SWOG advocacy chair. She’d been chosen to interview for the role of the group’s kidney cancer advocate.

A few weeks later, she walked into the Hyatt Regency Chicago to attend her first SWOG meeting.

At the genitourinary cancer meeting, committee Chair Ian Thompson, MD, was talking about S1500 and noted that of the 147 people enrolled, only two had a complete response to trial treatment. And one of them, he said, is right there.

He pointed to Laura. She stood up.

Monty Pal was in the row of seats in front of her. He turned around.

They hugged.

“It was such a fan girl moment,” she said. “It was so emotional.”

A SWOG trial had saved her, but it was Hope that allowed her to meet the researcher behind that study, and to join the team creating cancer clinical trials that save the next generation.

***

Monty Pal, MD

Monty Pal, MD

Nicholas Vogelzang, MD

Nicholas Vogelzang, MD

Laura Esfeller

Laura Esfeller

Acknowledgements

Thank you to everyone interviewed and involved in the telling of this story.

Thank you – especially – to Wendy Lawton, who worked closely with Hope staff to bring this anniversary piece from concept to creation, and who spent many hours researching and writing these chapters.